(How proteins are made in the cell from DNA code — image from here)

I’m fascinated by the fact that we are of this time but not really of this time. Our genes have a long and storied lineage. We carry in our bodies instructions and stories from a long time ago — and also memories, mythologies, traumas, wisdom.

We only think we’re “modern” because most of us live among skyscrapers and listen daily to the screech of car tyres on the tarmac. But we are really old. And our bones are capable of telling the oldest of stories.

It’s a privilege to be here then, isn’t it? To be so old and yet so new to this world.

*

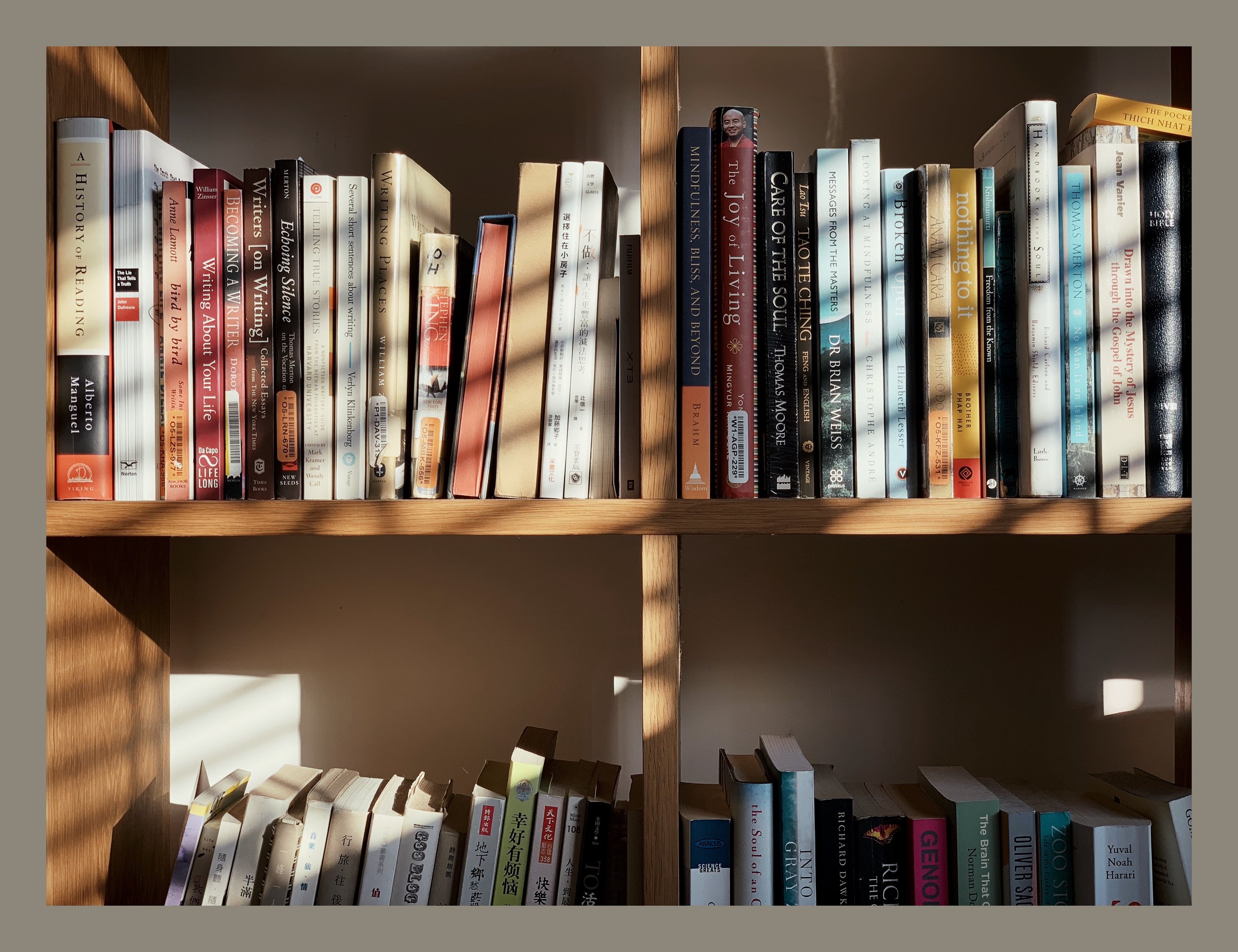

Writing is how we perpetually reach towards the part of our mind that is unconscious, automatic, old and hyper intelligent. It’s how we find our way back.

It’s how we can come to discover, track by track, trail by trail, who we are.

“Know thyself”, the ancient Greeks said. The idea, I believe, is not to fully resolve all the mysteries but to simply enjoy the journey of finding out who we are.

*

I didn’t enjoy science as a kid because I didn’t know better. I was not interested in the world outside of my own feelings and emotions. When I grew up I finally saw that science is a gateway to the spirituality I have always yearned for. The more I learn about the mind, the genes in my body, the invisible physical laws of the world, the hidden mathematics beneath the seemingly ordinariness of life, the more I come to see that there is more, much more, to the story.

Science is about discovery. It never rests on its laurels and declares any idea as being fixed. There is no finishing line in science because there’s always something to be discovered, some further understanding to be had.

Even though neuroscientists have made huge strides in understanding the brain — enough to do life-saving neurosurgery — still no one really knows where the mind is located. We still don’t understand the full picture of how consciousness can be created from physical material. And no scientist can tell you for sure that God or a Greater Consciousness doesn’t exist, because they know there’s always some further understanding to be had.

Maybe in the grand scheme of things we are still apes fumbling with our crudely-shaped tools, still a long way off from discovering fire.

*

Awe:

“I’m not saying that materialism is incorrect, or even that I’m hoping it’s incorrect. After all, even a materialist universe would be mind-blowingly amazing. Imagine for a moment that we are nothing but the product of billions of years of molecules coming together and ratcheting up through natural selection, that we are composed only of highways of fluids and chemicals sliding along roadways within billions of dancing cells, that trillions of synaptic conversations hum in parallel, that this vast egglike fabric of micron-thin circuitry runs algorithms undreamt of in modern science, and that these neural programs give rise to our decision making, loves, desires, fears, and aspirations. To me, that understanding would be a numinous experience, better than anything ever proposed in anyone’s holy text. Whatever else exists beyond the limits of science is an open question for future generations; but even if strict materialism turned out to be it, it would be enough.”

– “Incognito”, David Eagleman